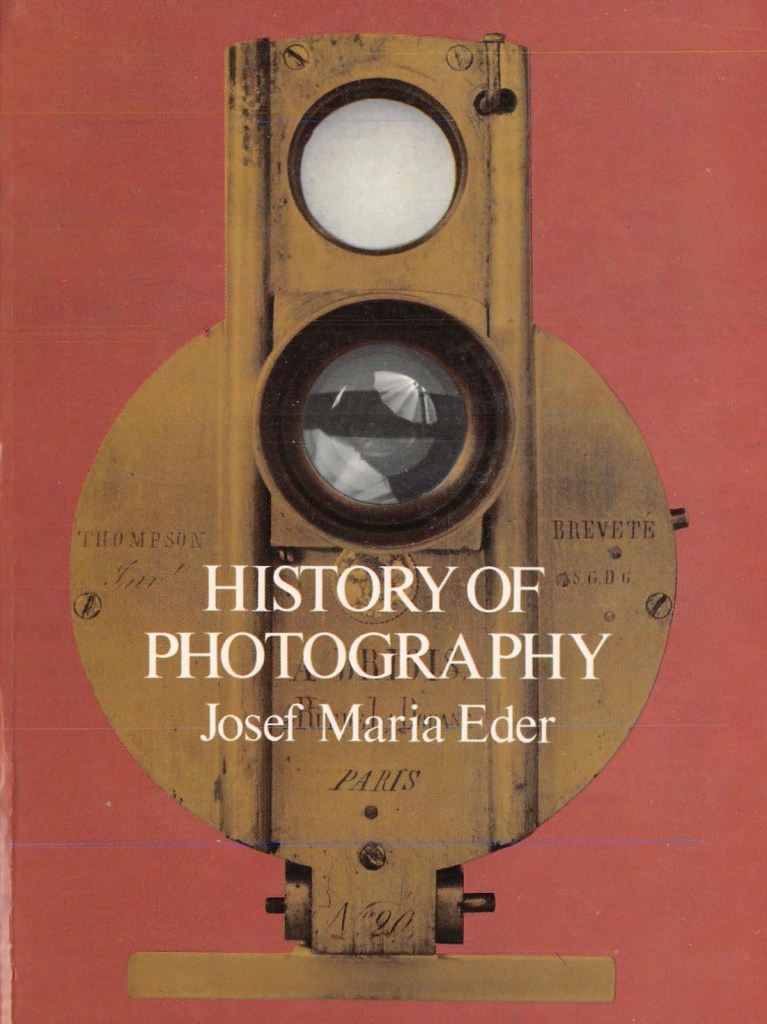

Fotoquímica – JM Eder

Chapter I – AFROM ARISTOTLE (4 aC ) TO THE ALCHEMISTS

Nature of visión – Acording to Wiedemann (Geschichte der Lehre von Sehen), there were two main schools of thought among the Greeks about the nature of vision. 1. Plato (427?-347? B.c.), held that sensitive threadlike rays are emitted from the eye and that the objects perceived are touched by these rays – analogous to the sense of touch. 2. Aristotle (384-322 B.c.) and Democritus (d. 370 B.c.), taught that the objects themselves emitted the light rays which meet the eye. Euclid (fl. c. 300 B.c.) and Ptolemy (fl. A.D. 127-141) accepted it. The opinion of Aristotle prevailed; the transmission of light has been affirmed in modern times.

Averroes (Ibn Ruschd, 1126-98) «Since one arrives at the same result in the study of perspective, one can accept either view; but as writings about the soul demonstrate that vision is not produced by rays proceeding from the eye, it is more fitting to adopt this last»

Lenses – The knowledge of convex lenses and spectacles is also related to the theory of vision. Convex lenses were well known to the ancients, examples of quartz crystal or glass lenses having been found at Nineveh, Pompeii, and elsewhere. It is supposed that they were used as magnifiers or burning glasses, as indicated in the writings of Pliny and Seneca.The first indisputable mention of spectacles is presented by Roger Bacon in 1276 (Emil Bock, Die Brille und ihre Geschichte, 1903 ; Emil Wilde, Geschichte der Optik, 1838 , p. 92 ).

Effects of light – It is taken for granted that the earliest observations of the influence of sunlight in affecting a change of matter (changes in organic substances) were made on plants. Knowledge of the fact that sunlight is necessary to the formation of the green coloring matter of plants is as old as the human race. «Those parts of plants, but in which the moisture is not mixed with the rays of the sun, stay white . . . . So all parts of plants which stand above ground are at first green, while stalk, root, and shoots are white. Just as soon as they are bared of earth, everything turns green . . . . Those parts of fruit, which are exposed to sun and heat become strongly colored.»5 He was also familiar with the action of light on the coloring of the human skin.

EARLY ANTICIPATIONS OF THE EFFECT OF LIGHT ACTION

Sophocles (495-406 B.c.) mentions in his poem «Trachinierinnen» a light-sensitive substance which required the employment of a dark room (verse 69r) and was to be kept away from sunlight in a light proof box (verse 692). Dejanira prepared from Nessos’ blood a love philter for her husband Hercules, by anointing a woolen undershirt. She was instructed by the dying centaur to make her preparations in the dark, fold the garment, and place it carefully in a chest. She cast aside carelessly, but some of the wool left over. As soon as these were struck by the rays of the sun, they disintegrated into a mass of flakes and emitted fumes. The narrative is so realistic that one can’t but feel that Sophocles knew something of the destructive effect of sun light on wool.

It is easier to connect the fancies of the Roman poet Publius Papinius Statius (A.D. 40-96) with photography, in anticipation of the daguerreo type process. A poem entitled «The Hair of Earinus.» The Frankfurter Nachrichten in 1928 reported that this poem mentions an image formed by light on a mirror of gold. «Then a boy from the throng, who, it chanced, had brought on his upturned hands a splendid mirror of gold studded with jewels, said: «This also let us give to the temples of our fathers; no gift will be more pleasing, and it will be more powerful than gold itself. Do you only fix your glance upon it and leave your features here.» Thus he spoke and showed the mirror with the image caught there.»

The poet thought that Cupid, by his divine power, had quickly engraved a portrait of Earinus on the surface of the mirror as he gazed on it, as anticipating Daguerre’s invention.» The picture of Earinus, formed by light, a bold dream of classical poetry, touches the imagination of today as a prophecy.

KNOWLEDGE OF THE ANCIENTS ABOUT THE ACTION OF LIGHT ON MATTER

Two thousand years ago the destructive effect of light on certain colors used in painting, especially on cinnabar, was well known. Vitruvius (first century B.c. ), a celebrated Roman architect under both Caesar and Augustus, writes in his»De architectura» (vii.9),the only work of this kind which has come down to us from antiquity, about cinnabar (minium) : «When used for trimming draperies in rooms not open to sunlight, it will keep its color unchanged; but in public places (peristyles, auditoriums), and in similar places where the light of sun and moon has access, it spoils at once exposed to their rays and the color loses its vividness and brilliancy, turning black.»

Another writer, Faberius, who desired to decorate his house on the Aventine, had a similar experience. He covered the walls of the peristyle with cinnabar, but after four weeks they were so unsightly and spotty that he had to cover them with another color. But if one wishes to bestow more care on the coating of cinnabar, to give it permanent, this can be done by first allowing the painted wall to dry and then, using a bristle paint brush, covering the wall with a mixture of molten Punic wax and oil, known to the Greeks as «kausis.» This wax coating permits no penetration by the rays of sun or moon. Vitruvius (vi. 7 ) discusses in detail the question toward which point of the compass a building should be erected and remarks that picture galleries, textile workrooms (plumariorum textriniae), and the studios of painters should face northward, for the colors used in such places should stay unchanged.

It is very doubtful whether Pliny ( first century A.D. ) intended, as many authors report, to refer to the darkening of silver chloride in light when he states that «silver changes its color in mineral waters as well as by salt air, as, for instance on the Mediterranean shores of Spain» (Historiae naturalis xxxiii. 5 5, 3 ) . I believe this reaction was undoubted ly assisted by the presence of hydrogen sulphide. Elsewhere (xxxvii. 1 8 ) h e says: «It is curious to note that many emeralds deteriorate in time; they lose their green color and suffer a change under sunlight.» On the other hand, a knowledge of the change of colors by light is clearly indicated in the next quotation from Pliny (xxxiii. 40) : «The effect of the sun and moon on a coat of minium (cinnabar? ) is injurious.» This statement is copied almost verbatim from the work of Vitruvius. Similarly, in his statement about the wax covering as preven tive of destructive light action, Pliny (xxi.49) closely follows Vitruvius. He speaks of bleaching wax «in the open air by the light of sun and moon» and discusses those ways of encaustic painting which use wax melted by heat and applied with the paint brush: «a method of painting which, when applied to ships, does not suffer the least change from sun, salt water or the weather» (xxxv. 4 1 ) .

No further statements about the change of other colors are to be found in the early accounts, which is perhaps explained by the fact that they made little use of colors other than red. According to Pliny xxxii. 7, 117), red paint was for long the only color employed in the execution of old pictures called monochromata, and it was especially minium (Pb3, 04, red lead oxide) and rotel (mixture of ferrous oxide) which were used. Even at a later period, when the primitive method of painting had been abandoned, the use of luminous colors, red and yel low, still predominated, though now painters employed four colors, as Pliny relates (xxxv. 7, 50) : white, black, red, and atticum, a color simi lar to ocher.9 Dioscorides describes, in chap. xxxii of the first book of his work De materia medica, the process of bleaching oil of turpentine: «Take some of the lighter kind, place it in the sun in an earthen vessel, mix and stir it violently until scum is formed, whereupon add resins and, if necessary, expose it again to the sun.

But, new researches have been made respecting the colors used by the ancient Romans; the material for these researches was found at Pompeii.10 Their constituent parts were mostly yellow and red ocher, vermilion, minium, massicot (lead oxide), mountain green (basic cop per carbonate), some kind of smalt, carbon, and oxide of manganese. Of all these colors, cinnabar was, perhaps, particularly suited to demon strate a change in color when exposed to light. It is not easy to under stand why these writers didn’t investigate and record further their observations of the changes in dragon’s blood and indigo blue, which colors, but little used, were undoubtedly known at that time.

Chapter II. INFLUENCE OF LIGHT ON PURPLE DYEING BY THE ANCIENTS

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.